A Dram with Dave Broom

Having covered Scotch whisky from its late 20th-century dip, through its extended boom years and beyond, the prolific journalist, author and broadcaster, Dave Broom, takes the long view. He shares a few thoughts on its future with Tom Bruce-Gardyne …

In search of an analogy for the current state of Scotch whisky, Dave Broom heads to the other side of the world. "It's a bit like Charlie's boys, rowing across the Pacific and being hit by tides from every direction, he says of his friend and fellow-whisky writer, Charlie Maclean whose sons have been battling huge storms. They are currently somewhere near Tonga on their epic 9,000-mile charity row from Lima to Sydney.

As for the 'tides' hitting whisky - "You've got war, you've got tariffs and a generational readjustment on drinking alcohol," he says. "You've got the aftereffects of the Covid blip, a loss of consumer confidence and the effect of lots of the majors increasing prices too dramatically because they believed the good times would last forever."

He believes the industry is slave to a slow, twenty-year rhythm, having covered Scotch whisky for decades as a prolific journalist with a stash of books and a number of films under his belt. "Whisky's cyclical," he says. "We all know that, but the reality of the cycle hasn't necessarily hit home. "We both agree that only when industry bosses desist from their mantra of premiumisation will it be clear that the message has finally got through.

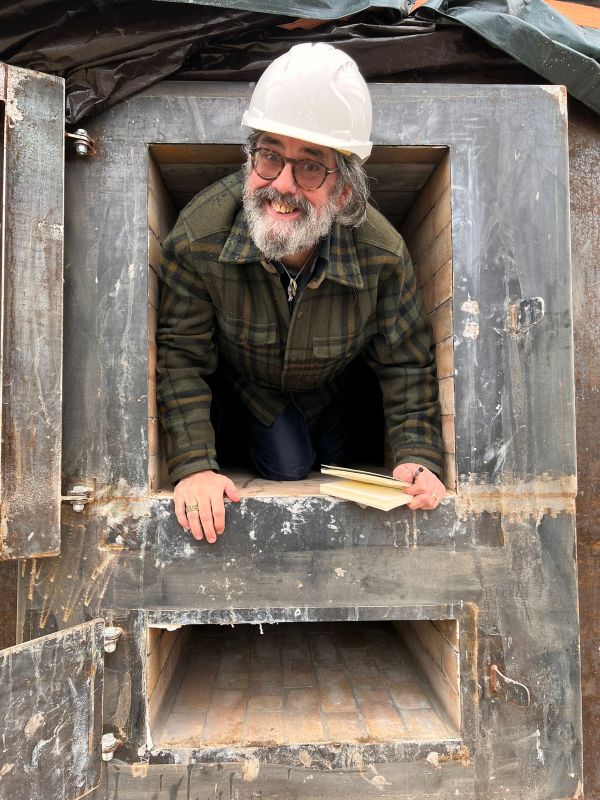

.jpg) Photo Credit - Till Britze

Photo Credit - Till Britze

"Premiumisation used to mean trading up from Johnnie Walker Red to Black," he says. "Now it seems to be 'Oh, you have to spend £3,000 on a bottle'. I think the industry just became starry-eyed." Some might call it greedy.

Dave Broom has his own 'Tinkerbell theory' based on the pantomime version of Peter Pan where Tinkerbell is kept alive by the audience shouting "I believe in fairies". "I can understand why a bespoke suit costs a lot of money because of the care and design, and everything that goes into it," he says. "Whisky is not inherently a luxury product. The stills are not made of gold. The casks used are used by the entire industry. The only thing that elevates whisky is probably time, as in age and scarcity."

"As soon as you take those two elements away, and say 'it's luxury because we say it is', which a lot of distillers are doing, then you're playing with fire because people will eventually say 'I don't believe in fairies, anymore'."

Whisky's secondary market played a big role in this, initially by teaching the industry the true value of its aged, rare stocks. When Diageo released bottles from its then-closed distillery of Port Ellen for £140 in 2007, it found they were being sold for double that amount at auction within weeks. By 2014, the release price for the same whisky had soared to £2,200 to close the gap.

For now, this arms race has stalled. "People are not buying at the very top end," says Dave. "I think the market has been so skewed towards super-premiumisation, that the image of Scotch in particular, shifted in people's minds that whisky was a super-expensive spirit." Dawn Davis at the Whisky Exchange made a similar point about the endless launches aimed at the richest 1%.

In the past, the issue was much more with the bottom-end, and Dave is hoping the industry will not repeat "the mistakes of the 1980's and 90's, in the belief that the only way to sell whisky was by slashing its price." The thought of another race to the bottom, purely in pursuit of market share, is chilling.

"On a less negative note, in the 1970's and 80s there was a generational rejection of whisky," he says. "People were saying I'm not drinking my dad's drink, and they discovered vodka. I don't see that happening now. The younger generation is looking at whisky. They're still drinking, but on different occasions and in different ways."

Photo Credit - Till Britze

Photo Credit - Till Britze

A few weeks ago, at the World Whisky Forum in Bordeaux, he says "the consensus in the room, was that the good times had gone on for so long, that sales people didn't try and sell, all they did was take orders. Now, the industry has to learn how to sell again. It's got to go out and speak to consumers and see what they want, flavour-wise, serve-wise and also what price they are willing to pay for the whisky."

In his view: "The whisky industry has always been built by the mainstream, and I think the majors forgot that." We get on to Diageo, which spends vast sums on its beloved Johnnie Walker, whose marketing may suffer from diminishing returns like some great Zeppelin with a leak that needs ever more gas to keep it airborne.

He does feel for these publicly-listed players and the way they are structured. "They have investors who need to see profits every quarter," he says. "Therefore, the thinking that operates within these companies is short-term, and is almost based on an FMCG model, and whisky is long-term. So, it is kind of incompatible."

"In many ways I sympathise with the situation the big companies are in, but the way that they are trying to get out of it is deeply worrying," he says. As an example, he cites Diageo's recent cost-cutting decision to close its Roe & Co. distillery in Dublin. "If you get the biggest distiller pulling out of the Irish category altogether, what signal does that give to the city, to investors, to banks …?"

The overall positive to draw from his critique of the industry, is that many of its problems are self-inflicted and thus eminently fixable. And on a production level, in terms of the quality of spirit and the creativity of distillers, Dave still believes Scotch whisky is in a good place.

_0.jpg)

Award-winning drinks columnist and author Tom Bruce-Gardyne began his career in the wine trade, managing exports for a major Sicilian producer. Now freelance for 20 years, Tom has been a weekly columnist for The Herald and his books include The Scotch Whisky Book and most recently Scotch Whisky Treasures.

You can read more comment and analysis on the Scotch whisky industry by clicking on Whisky News.