An Indian Take on Tariffs

As the Scotch industry celebrates its biggest victory in years – the decision to cut India's import tariffs in the near future, Tom Bruce-Gardyne lifts the lid on this vast, complex market and gets the views of two Indian distillers …

You can almost taste the pent-up demand for Scotch whisky in India. Despite those eye-watering tariffs of 150% that have been in place since 2007, the country has grown to become its biggest market by volume. The question of how much it will explode once those tariffs are halved is tantalising. Following the recent FTA deal between India and the UK, the drink will suddenly become affordable to millions of new consumers.

It is a heady prospect for the industry, but for now a little patience is required. The deal has to be ratified by both governments and that might take until early next year, possibly longer. To gain a different perspective on what might happen on the ground, I spoke to two leading Indian distillers.

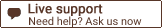

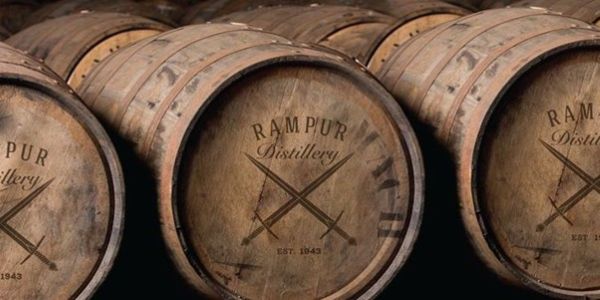

"We are one of the largest importers of bulk Scotch malt, so any reduction in duty is definitely going to help us," says Sanjeev Banga, president of international business at Radico Khaitan whose 8PM brand, was the fifth biggest Indian whisky with sales of 12 million cases in 2022.

"There are two ways to look at it," he says. "You can increase the percentage of Scotch malt in your blends and further premiumise your portfolio, or you can have savings on your cost." At present nearly 80% of Scotch exports to India are in bulk much of which is blended into Indian whisky brands. While that could change if distillers switch to bottling more in Scotland to add value, he is not worried about supply at present.

Indian whisky-makers were disappointed not to get a minimum import price as part of the FTA deal to prevent Scotch being dumped on the market. "I think that will happen," says Rakshit Jagdale, MD of Amrut Distilleries, home to one of the top Indian single malts. "With Scotch exports down 15-20%, and especially down in the US, I think cheaper Scotch will come into India."

Overall, he holds with his prediction of two years ago that Scotch volumes might treble in India with the cut in tariffs. But he is also hoping for a more level playing-field at a state level. Apparently big states like Maharashtra, home to Mumbai, impose 150% levies on imported brands, and 300% on home-grown whiskies.

Every brand in every state has to pay an annual license. Jagdale claims that in the state of Haryana, near Delhi, it is 50,000 rupees (£432) for the likes of Johnnie Walker Black Label, and 900,000 rupees (£7,786) if you're an Indian whisky. "It's the highest form of insult to any Indian distiller, that in our home country we are being discriminated," he says.

He believes it's down to the lobbying power of the trade body ISWAI, to which all the big foreign players like Diageo, Pernod and Bacardi belong. Another issue he wants addressed is transfer pricing, whereby big distillers in Scotland may have been undervaluing the true value of their shipments to evade some of that punitive 150% import tariff.

For a simplistic analogy it is like that well-known trick for avoiding Ryanair's punitive excess baggage fees where you unpack a few clothes before the gate and put them on, squish down the bag, slip through and re-pack on the other side.

According to Jagdale, a £100 case of Scotch would be billed at maybe £50 to the distiller's Indian subsidiary as it passes through customs. The difference would be recouped in a high mark-up. How much it has been going on is clearly unknown, but you can see the incentive.

In 2022, Indian authorities demanded US$244m from Pernod Ricard India for undervaluing its imports from 2010-20. The case and others facing the company are ongoing, and Pernod Ricard strongly denies any wrongdoing by its employees.

Meanwhile, back in the market, when the cut in import tariffs happens, the big Scotch players plan to pass on the savings to consumers. In Bangalore a bottle of Johnnie Walker Red currently sells for the equivalent of £23 compared to £15 for Blender's Pride, a top-selling Indian whisky. Reduce that £8 gap significantly, and Indian consumers will trade up to Scotch.

That is the industry's assumption, but Sanjeev Banga is not so sure given the improvement in Indian whiskies whose drinkers have become better informed. "Those days are gone when if it was an imported Scotch, the Indian consumer would lap it up," he says. "Now, the Indian consumer is more concerned with the quality of the liquid more than just the brand-name."

It sounds quite a generalisation, but he may have a point, certainly at the top end. "Now there's a lot of pride and passion about the super quality of Indian whiskies, especially Indian single malts," he says. "A few years ago, there were no top-class Indian single malts and Scotch was obviously ruling the roost. Now we are world-class."

At Radico Khaitan, his single malt is Rampur which is doing very well in India, and all over the world, apparently. The category was pioneered by Amrut Single Malt which was launched in Glasgow way back in 2004. Ashok Chokalingam, now head of distilling, calls Amrut "the missing link between Scotland and Kentucky" – the former a reference to the pot-still distillation, the later to maturation in a hot, humid climate.

But the good news for whisky-makers in Scotland and India, is that this vast market is set to keep growing. "We are already the fourth largest economy in the world, and soon to become the third largest," says Banga. "The disposable income within the population is getting better by the day."

Award-winning drinks columnist and author Tom Bruce-Gardyne began his career in the wine trade, managing exports for a major Sicilian producer. Now freelance for 20 years, Tom has been a weekly columnist for The Herald and his books include The Scotch Whisky Book and most recently Scotch Whisky Treasures.

You can read more comment and analysis on the Scotch whisky industry by clicking on Whisky News.