For Peat's Sake

The bitter-sweet tang of smoke has been part of Highland and island whiskies for centuries. It all but defines Islay malts, and yet peated whiskies may become an endangered species if a peat ban comes into force. Ian Fraser investigates …

Mark Littler, the independent whisky consultant and broker, recently set the cat among the pigeons for the Scotch whisky industry with an article in Forbes magazine headlined Peated Scotch Whisky At Risk Of Ban Within 5 Years.

In this, he cited the Canadian-born environmental consultant Alastair Collier as saying: "Peated whisky is absolutely at risk of being banned. There's a significant risk within the next five years, and a high risk within ten years."

However, the industry warns that any blanket ban on the use of peat would be hugely destructive to the entire Scotch sector. It would bring an end to some of its most iconic single malts, such as Ardbeg, Caol Ila, Highland Park, Lagavulin, Laphroaig, Port Charlotte, and Talisker – as well as costing thousands of jobs in remote rural communities.

In its response to the Scottish Government consultation on the topic the Maltsters' Association of Great Britain said that ending peat usage "would only be possible if a viable alternative to peat was found that gave the same flavour profiles and was acceptable for use within the regulations that exist for Scotch whisky production. Although research is taking place, this is not looking to be a likely prospect for some time."

.png)

The issue, however, is that, as we explained three years ago, peatlands form one of the world's most efficient carbon stores, globally sequestering approximately 550 billion tonnes of carbon, roughly 30 times more per hectare than a healthy tropical rainforest. Extracting peat means the peat bogs first have to be dried out, which essentially means killing them and releasing all the carbon they store in the shape of CO2 into the atmosphere, fuelling climate change.

Peatlands also provide a habitat for many rare species, including swallowtail butterflies, hen harriers and short-eared owls, while preventing flooding and filtering water. Meanwhile, abuse of peatlands in recent centuries means that 80% of UK peatland has been designated as degraded by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) – versus a global average of 12%.

Littler also warned that, even if the whisky industry were to secure the exemption it craves from a future ban, it will face reputational harm if it continues to use extract peat. He wrote: "Up until the recent bans of peat use in horticulture, the industry accounted for only 1% of peat usage in the UK. But that figure is expected to rise to around 40% over the next three years as further bans are introduced in other industries. Scotch's usage won't likely increase, but its share of total usage will grow significantly."

Most industry observers agree that he has a point here, but where the article falls down for many is when Littler mentions alternative substances which might be capable of mimicking the compounds that give whisky its smoky and peaty flavours.

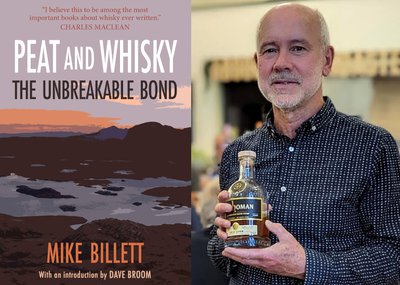

Mike Billett, a former professor of biogeochemistry and environmental change at Stirling University, who has spent three decades researching peat, says: "The composition of the phenolics produced by burning peat are unique to peat – and even in some cases unique to individual peat bogs." Billett, author of ‘Peat & Whisky: The Unbreakable Bond' was disparaging about the suggestion that "biochar", a high-carbon form of charcoal, might be some kind of magic bullet, saying: "That just isn't a viable alternative."

And Arthur Motley, former MD of Royal Mile Whiskies who recently set up the Motley Spirit Agency says "I'm not a scientist, but I don't think it's going to be possible to recreate flavours that make a smoky, interesting, delicious whisky without using peat.

Ruth Piggin, Industry Sustainability Director at the Scotch Whisky Association (SWA), says: "The industry is open to and investing in research that may one day yield an alternative that is [a viable alternative to peat] from a flavour and sustainability perspective, despite an alternative not being legally or technically possible at the present moment."

Yet Billett is unequivocal, and says: "I can't see Scotch whisky being made without peat. It wouldn't be Scotch whisky any more – peat is part of its DNA. Around 80% of Scotch whisky is either peated or has peat as an essence." However, he concedes that whisky can be made without peat, and that distilleries such as Nc'Nean have proved this.

.png)

He advocates a "joined-up approach to the peat problem which brings everybody on board," including peat suppliers like the Northern Peat & Moss Company, maltsters, and the distillers. He also thinks that the SWA is too prescriptive about how Scotch whisky is made.

"There are distillers in Scotland which would like to use other materials to produce smoke, but the SWA's rules don't allow that. The rule is if you smoke your malt, you've got to use peat." Billett says this is giving distilleries elsewhere in the world, where rules are more flexible, an unfair advantage. "Being open-minded about it would be the right way forward - the rules are really, really tight."

He disagrees with suggestions that extracting and burning peat are "climate crimes", a claim made in the Forbes article, saying: "If you want to talk about what is damaging Scottish peatlands right now – and about 20% of Scotland's land area is peatland – what's damaging it the most is extreme weather, fire, drainage, overgrazing and forestry. The whisky industry is a minute contributor."

Overall, Billett says the way forward is for the whisky industry to "embrace peatland restoration…. Peat is a soil, and, in my opinion, it's a renewable soil. Peat grows at about one millimetre a year in Scotland. The way forward involves having an aftercare agreement for peatland."

Billett praises Suntory Global Spirits - owner of Laphroaig, Glen Garioch, Bowmore, Auchentoshan and Ardmore - for its efforts in this area. "They're doing exactly the right thing, putting carbon back into the soil and restoring peats and locking up carbon faster than they use carbon. That's fantastic, and other producers are catching up."

However, according to Bristol University geochemists, Toby Ann Halamka and Mike Vreeken, peatland restoration isn't going to be enough. "It's been suggested that the whisky industry can offset its peat degradation by investing in peat restoration. But peatland restoration is a long-term and imprecise solution that might take decades to assess properly, while existing peatlands are needed as a natural carbon sink now."

If there is going to be a ban on peat use by the industry, Motley predicts a bifurcation in the aftermarket for rare and aged single malts. "We're going to get this evolution into a pre-peat and a post-peat word. Suddenly, there will be a rarity value attached to a peated whisky, made at a time when peat was plentiful."

_0.png)

Ian Fraser is a financial journalist, a former business editor of Sunday Times Scotland, and author of Shredded: Inside RBS The Bank That Broke Britain.